The Dutch police have experimented with body cameras in Amsterdam during the years 2017 and 2018. Following a 12-month impact assessment, the conclusion is that the cameras reduced violence and aggression against police officers.

About this page

The experiment, the impact assessment and the results are described in a book – in Dutch, but with a management summary in English. On this page, you can read that summary supplemented with some additional information, including the most important graphs and pictures. The book can be downloaded for free (as pdf or e-book) – see the links below.

The experiment

This experiment with bodycams – or Body Worn Video/Body Worn Cameras as they are also called – was conducted in the regional police unit of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. It involved one-hundred bodycams that were available to all 1,500 front-line police officers. The experiment was one of over thirty pilot projects in the country, intended to determine whether body cameras should become standard kit for police officers. Each pilot had its own goal: in Amsterdam, the main purpose was to improve the perceived safety of frontline police officers. The second goal was to reduce the use of violence and aggression against the police.

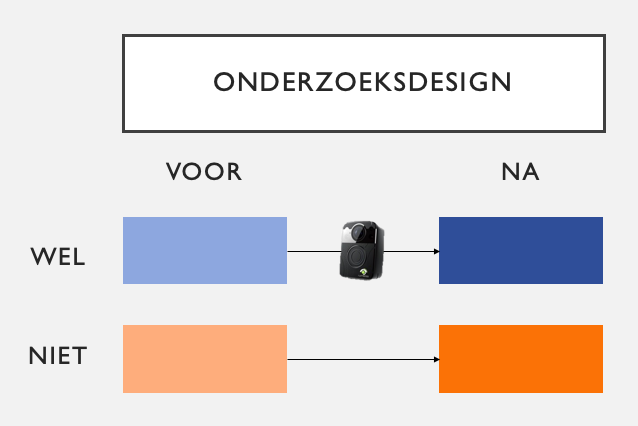

Study design: RCT

This impact assessment meets the requirements of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) supplemented with a focus on mechanisms and context. This is the first study with this rigor that was conducted in The Netherlands.

Six teams with bodycams – the treatment group – were compared with four teams without bodycams – the control group. Allocation to the two groups was random. For both groups, data on violence and aggression against police were collected for the 12 months preceding the introduction of the bodycams and the 12 months afterward.

Over a thousand questionnaires were completed and nearly one hundred in-depth interviews were conducted. In addition, internal registrations of violent incidents against police officers were analyzed, as well as log files with data on the usage of the cameras and the number of recordings. The researchers have gone on several ride-alongs with officers to observe how the body cameras work in the field. In one of the twenty units within the Amsterdam police force, additional Action Research had been done. We designed an intervention with extra activities to find out whether a maximum amount of communication and guidance would stimulate the use of body cameras, and increase the awareness of and compliance with internal guidelines.

The device itself

First we asked users about the technology itself and found that most users were satisfied with the performance of the body cameras, including the underlying hardware, software and data-connections for the storage of recordings. There were complaints about battery-life and about the fact that recordings were not accessible – this was a choice made by the management – for the officer who made the recording.

Personal safety

The first empirical outcome of the study pertains to the perceived personal safety of police officers. In the six teams with body cameras this experience of safety improved slightly compared to the period before the body cameras were installed. In the teams without body cameras – the control group – the perceived personal safety did not change. When we move the analysis from the level of the entire team to the level of individual officers, the pattern becomes more apparent. Officers who use the bodycam on a daily or weekly basis feel safer than their colleagues who did not use the bodycam. Of the officers who regularly wore a body camera, fifteen percent felt safer than three months previous. Perceived personal safety is hard to operationalize in surveys, and the in-depth interviews provided in the full report add valuable insights to the statistical findings.

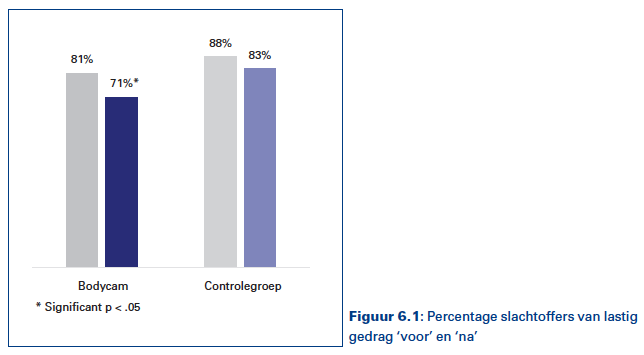

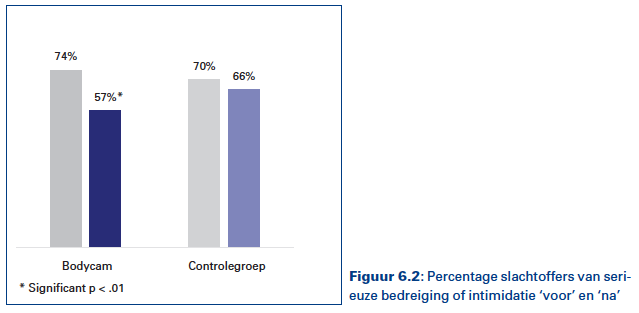

Violence against police

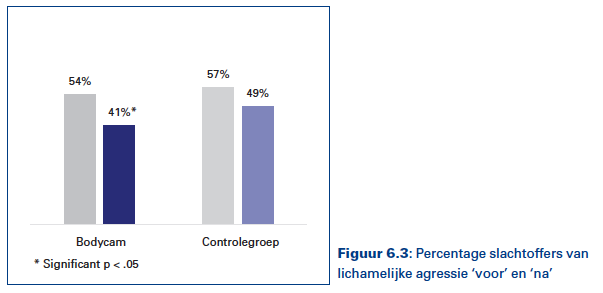

Violence against police officers, the second effect-indicator we investigated, has significantly decreased in teams with body cameras and no change was found in the control group. This is true for all three indicators: annoying behavior, serious threats, and physical aggression. Looking at serious threats, for instance, the percentage of victims among officers in the treatment group dropped from 74% to 57%. This justifies the conclusion that the body cameras were the cause of the effect found.

Who is influenced: the public or the police?

We now know that the body cameras ‘worked’, but we don’t yet know how they worked. The ‘black box’ of the experimental set-up does not explain why the effect occurred. Therefore, we will need to open it up, and that is exactly what was done in this study. In general terms, we heard that most police officers assume that any civilizing effect of the body camera will manifest itself mainly on the side of the public and not in their own behavior. They notice that citizens can become less aggressive. However, they do not see similar effects of increased self-awareness in their own behavior. We did, however, find that fifty percent of officers believe that body cameras will lead to more professional policing. Much more is said about the untangling of these complex interactions, but in general, the conclusion seems justified that the deterrent effect of the bodycams worked in two directions. The decrease in violence towards police officers was most likely caused by a combination of ‘cooperating citizens’ and ‘professional police.’

About the recordings

In this study, we also looked at the number of recordings that were made and the number of times they were used (and why). The report describes this, but the findings cannot be generalized because the use of recordings for the duration of this pilot in Amsterdam was not encouraged by the management of the Amsterdam police. At the outset of the pilot, it was made clear that recordings could only be used for criminal investigations, internal disciplinary investigations or complaints against police officers. This policy choice has reached the front-line officers: relatively few recordings were made, and hardly any recordings have been reviewed at all. Many officers we interviewed thought of this as a ‘missed opportunity’ and pointed at the value they believed recordings could have for evaluating police practices or for coaching and training purposes. Had internal policies been different, probably a lot more recordings would have been made and used. This will have to be examined more thoroughly in follow-up projects.

Guidelines and policies

The guiding principle in this pilot was that officers had substantial discretion in deciding whether to wear a body cam and in what to record. This means that the results of this study are difficult to generalize: nobody knows what will happen if the internal guidelines become stricter. In Amsterdam, almost all officers knew what the bodycams were supposed to do (make us safer), but hardly anyone knew exactly how the cameras were supposed to make that happen.

One-in-four officers did not receive training for the operation of the bodycam; one-in-two did not receive instructions on the guidelines and legal framework. This lack of training negatively impacted the level of compliance with the rules: two-in-three officers filmed inside homes, even though the policy clearly stated this was not allowed. Three-in-four officers reviewed the recordings on the screen on the back of the body camera before writing their reports, something that was not allowed either. Moreover, many officers were unaware of who could get access to footage, and many were worried about this aspect. They feared their recordings could also be used against them, which will have made many officers reluctant to make recordings at all.

Experiment within the experiment

Pilots never fail, but pilots never scale. Results are often positive if they are based on early adopters, but what happens if you ‘roll-out’ to the entire police force? To find out how this impacts on the key findings, we selected one team within the Amsterdam police force where we conducted a ‘pilot within the pilot.’ In that team, we decided that all officers were required to wear a body cam each time they went out onto the street. They could still decide what to record, but the bodycam had to be worn at all times. For six months, we did everything we could think of to boost the use of body cameras. Individual training, newsflashes, quick fixes of technical issues. The change in policy from voluntary to mandatory, combined with the supporting efforts described, had extraordinary results. The use of body cameras increased six-fold in just three months. The officers were more familiar with the guidelines than in any of the other teams, and they complied with them more than anywhere else. The main ingredient in the mix that produced this result was the presence of three ‘core-instructors’: colleagues who were available to answer any questions, to alleviate fears and concerns, and to fix technical issues as soon as possible, thus preventing negative stories from circulating.

Beware of ‘rolling out’

This study proves that body cameras decreased violence against police officers. For other organizations considering the introduction of body cameras, it is of vital importance to compare their own context and mechanisms to the ones in Amsterdam. There will never come a time when we can answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question of whether body cameras ‘work’ or not. First of all, we need to determine what is meant by ‘work.’ Reducing aggression towards officers is not the same as, for instance, an effort to reduce use-of-force by the police. Second, the context will never be exactly the same. That does not mean the results are only valid in Amsterdam. What it means is that the context will have to similar enough to be able to reach similar results. This pilot was in Amsterdam and was done by front-line police officers. The experiment was aimed at activating the preventive mechanism body cameras can have: through increased self-awareness and deterrence. If other mechanisms are activated, and especially if this happens in other physical, technical and policy contexts, the results may very well be different.

Nonetheless, we can learn a lot from this particular study. For the first time in The Netherlands, robust empirical evidence is now available that in the right circumstances with the right equipment and within this type of context, body cameras can significantly improve the safety of police officers.

About the book

The book – in Dutch – has been published by Politie & Wetenschap and SDU (ISBN: 9789012404631) and is available for download as pdf or e-book.

[This page was updated on 2 May 2019 to fix some translation issues. I would like to thank Ian Adams for his help.]